About the

Project

The Ely Green Digital Variorum (EGDV) is a digital humanities project and collaboration between the Center for Southern Studies and the Roberson Project on Slavery, Race, and Reconciliation at the University of The South.

The Director of the Roberson Project, History Professor Woody Register, has been leading the University’s investigation into its historical entanglements with slavery and slavery’s legacies since 2017. The Center for Southern Studies—led by English Professor John Grammer—was established the following year after receiving a generous grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to support digital efforts in scholarship related to inclusive, diverse, and enriching explorations of Southern history.

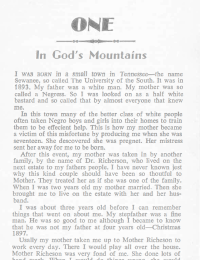

The EGDV explores the eras following the aftermath of the Civil War’s fractured nation, for Ely Green came of age during post-Reconstruction and Jim Crow on the very domain of a campus established to educate the progeny of Southern white enslavers. It only makes sense that Ely Green’s collection in the University Archives would become a collaborative focal point for Southern Studies and the Roberson Project. To formalize this convergence, Grammar and Register began working with digital humanities specialist Hannah Huber to un-edit Green’s story. The project supports the Roberson Project and Southern Studies missions in two important ways: 1) For Sewanee’s campus, it serves as a pedagogical tool that helps faculty and students grapple with a fuller picture of Sewanee’s past; 2) Beyond Sewanee, it serves as a model for using digital tools to reckon with a college or University’s past and its legacies of slavery, and to explore authorship, print history, and the living legacies of collections housed in institutional archives.

How It Began

In a May 2020 email to Huber, Register detailed the earliest vision for the EGDV: “What I would like to do is investigate digital ways to compare the various iterations, a kind of algorithmic way of exploring what happens when African American self-expression meets Southern white liberalism/moderation in the late era of segregation. The idea is to produce a digital variorum that enables an interdisciplinary engagement and interaction with the various texts as a way of examining how editors made it publishable and negotiated the meaning of race in converting it to ‘white’ English prose expression of authentic Blackness.” From this description, Huber began the project planning process, reviewing the materials in Green’s collection, determining the scope of the project, and carving a path forward, which turned out to be quite arduous (Just scanning the 1,200-page manuscript was a daunting task: Special kudos to previous member of the Roberson Project team, Cliff Whitfield, who served as the Digital Technology and Public History Coordinator, and who single handedly scanned all 1,2000 pages during the academic year 2022-2023!). In June 2022, the autobiography’s copyright holders: Patricia Ravarra, Ely Green’s granddaughter, and Em Turner Chitty, daughter of Arthur Ben and Betty Chitty, consented to the project.

“What I would like to do is investigate digital ways to compare the various iterations, a kind of algorithmic way of exploring what happens when African American self-expression meets Southern white liberalism/moderation in the late era of segregation.”

- Dr. Woody Register

Project Goals

- Explore the print history of Green’s story through an emphasis on authorship and bibliographic study

- Join digital efforts to preserve and explore Black authorship in autobiography

- Engage practices of public and community history with a particular focus on honoring the living legacy of the archival material

- Draw attention to Green’s Manuscript as a cultural and historical artifact that recovers one of the countless Black voices omitted from the official Sewanee narrative.

- Deemphasize authorship through a collaboration with colleagues and students

The Process

- Learned from inspirational projects

- Developed data management plan, including

- Naming conventions for file names

- Storage of scanned images and documents

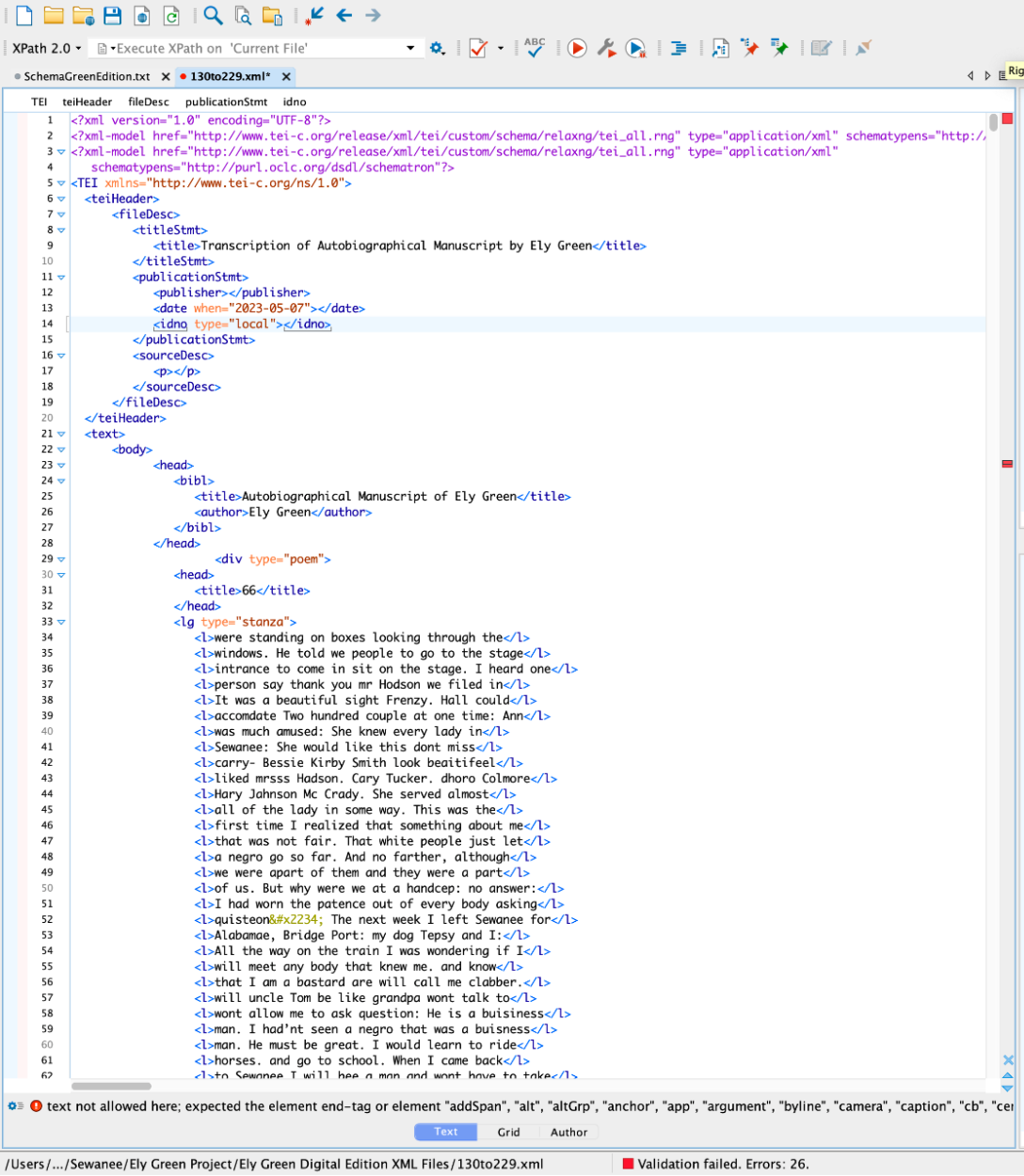

- Schema and format for encoding manuscript using TEI-XML

- Transcribed, compared, and encoded with students

- Finding Your Place program, Fall 2022: Transcribed manuscript and compared with printed editions

- English course, Spring 2023: Refined transcriptions and encoded manuscript

- Collaborated with digital humanities experts at Performant to build project

- Created custom website

- Built variorum via EditionCrafter

In the Classroom

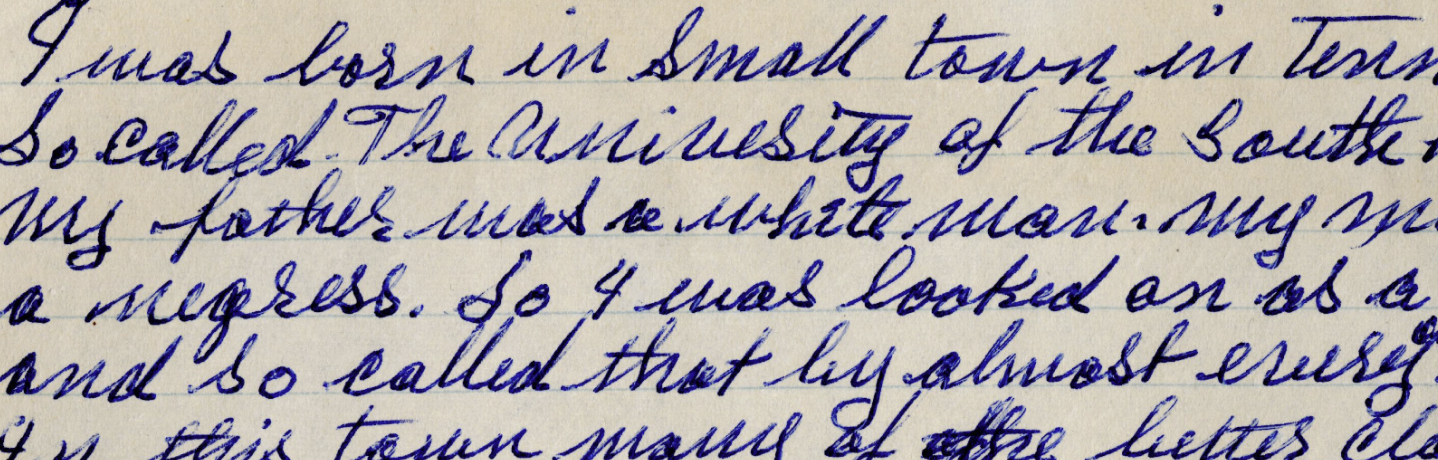

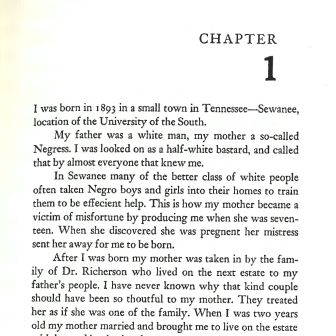

In Huber’s courses during the academic year 2022-2023, work on the variorum helped students gain skills in digital archiving and textual encoding and encouraged them to examine print history and authorship as they compared Green’s handwritten words to the books’ printed versions. First, students were tasked with exploring the content and insight of Green’s writing: for example, Green’s use of the regional dialect, the influence of literary legacies on his storytelling, and the ways in which Green anticipates and, at times subverts, reader expectations. Second, students compared how these aspects of his writing were impacted during the editing process of two different editions of his autobiography.

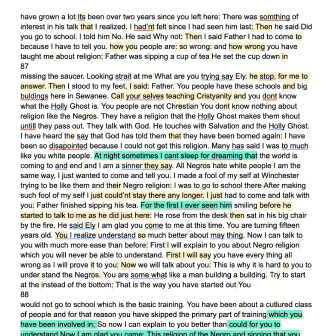

In Fall 2022, Huber led a class for the interdisciplinary program Finding Your Place, which emphasizes the study of place, community, and identity across disciplines. Early in the semester, students participated in a digitization day, where they informally scanned hundreds of pages of Green’s collection. They then used these images to begin the process of comparing the manuscript pages to its derivatives. Before they began comparing their assigned pages, students compiled an annotated bibliography to provide cultural-historical context for important references to persons, places, and events that will eventually be featured on the project website. This helped students better understand Green’s perspective and surroundings, as they explored the cultural-historical moments in which he was living. The next step was to determine the conventions of a diplomatic transcription of Green’s manuscript. Many questions arose: How do we deal with misspellings? How do we document Green’s idiosyncratic punctuation system? What about indecipherable letters or words? It was a challenge to come to a uniform answer to all these questions, but the combination of in-line comments and markup in Google Docs allowed for students to note challenges or detail their rationale for particular decisions made in the transcription process.

Navigating the differences between versions was no easy task and the assignment led to very stimulating discussion and discovery. For instance, students soon realized that there was no clear, standardized process for how either Press edited Green’s words. Sometimes, complete sentences were omitted, other times just words here and there. Sometimes, misspellings were corrected, sometimes they were not. Green tended to write in the vernacular with the clear intention of conveying the Black dialect of his region, yet that is what was most often corrected as a “misspelling.” Moreover, across the two derivatives, different things are changed. Unfortunately, there was no way for us to fully trace the editorial process in the records of Green’s collection. The Chittys did a fine job of saving the long sheets and galley proofs from the 1970 edition, which is more faithful to the manuscript (or at least to Elizabeth Chitty’s transcription of it), but there is little documentation of what the Seabury Press did to prepare the “Sewanee years” for publication. An example of the breadcrumb trail students followed in the Archives is a 1968 letter to Arthur Ben Chitty from an editor at the University of Massachusetts Press, which describes Seabury Press as having “novelized what they published” of Green’s Sewanee years. The editor expresses his intention to “maintain the integrity of the book” by not simply reprinting Seabury’s version of the autobiography’s first section. Instead, he tells Chitty he will get that section “back to the point where we are with the rest of the typescript.” Unfortunately, the University of Georgia Press chose to reprint the Seabury Press edition without alteration in 1990, and this is still the only edition of Green’s Sewanee Years that remains in print.

In students’ final presentations, several noted a common trend among editors to omit passages in Green’s writing when he is most introspective, particularly at moments when he is reflecting on his biracial identity and the discrimination he experiences. Moreover, across the students’ analyses, it became clear that some of the names of white people (in addition to Green’s father) were changed to protect the identity of their families. Students also noted an editorial tendency to correct misspellings when referencing—or in the dialogue of—white elites but to leave words misspelled when Green likewise referenced Black individuals. Through these impressive discoveries, students concluded that instances of omission, alteration, and pointed spelling corrections convey important insights about the effects of bias in the editorial process and other factors of literary marketplace, such as intended audience, on the censorship of Black literature.

I will highlight one student presentation that exemplifies the impressive work that all the students did in that Fall 2022 classroom. About midway through Green’s Sewanee Years, he describes a trip he takes to visit family in Alabama. For the first time, he attends a Black Baptist church. Having only had attended Sewanee’s predominantly white Episcopal church up to that point, Green is shocked by the difference. Typical of his inquisitive and verbose nature, the young Green assails his Uncle Tom with questions. Here is an excerpt from Green’s transcribed manuscript: “I started asking Uncle Tom about religion he soon got tired of trying to answer them. Then he said white people teach negros what they want them to know. That will help them to be more service to the white people. That’s why most negros is willing for them to have all this world: just give them heaven. When you are that way you are a good negro a should go to heaven.” Uncle Tom tells him to “forget all about the experience you had” at the white Episcopal church in Sewanee: “You will see why you will never be able to understand somthing that really not what you hear about: There are many religions and teachings of religions. Most people demonistrative as to their intelligence. That is why many people like us don’t display our feeling” (Italicized portions omitted from the 1966 edition). As the following student reflection explains, these insightful lines from Green’s recollections are omitted from the 1966 edition and edited still in the 1970 version:

“While both the 1966 and 1970 transcript had a great number of changes in the spelling and grammar along with a few changed names, the 1966 edition frequently omitted phrases and whole sentences from the original text. . . . Green very much wrote his autobiography as if he was sitting in front of us telling his life story, and the 1966 edition seems intent on removing elements of his manuscript that give it this style. But there is one . . . difference that highlights a particularly disturbing aspect of the 1966 edition, when Uncle Tom is telling Green about religion, he reveals to him how white people present Christianity in such a way that encourages Black people to value heaven more than any rights they would want to have on Earth, but the 1966 edition leaves out just enough of this section to make Uncle Tom’s message be something that can easily be glossed over. The changes in the 1966 edition seems fixated on removing Green’s personality from the work and on softening the hardships of biracial and Black children in Sewanee.”

This student’s discoveries reveal how these omitted statements by Uncle Tom align Green’s contemplation about racial identity in the U.S. South with reflections by literary giants of the time in which he came of age, such as Paul Laurence Dunbar’s 1895 poem “We Wear the Mask,” which decries:

We wear the mask that grins and lies,

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,—

This debt we pay to human guile;

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile,

And mouth with myriad subtleties.

Uncle Tom’s words also call to mind W. E. B. Du Bois’s description of “double consciousness”:

It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

As my student astutely observed, Uncle Tom explains that within the racist structures of the U.S. South, Black inhabitants are constantly pressured by the power structure of white religion (among others) to be “a good negro” and to not “display our feeling.” In doing so, Green voices through Uncle Tom a literary legacy of Black interior duality, one that parallels and underscores the specific struggles Green faced in his experiences as a biracial youth in the South.

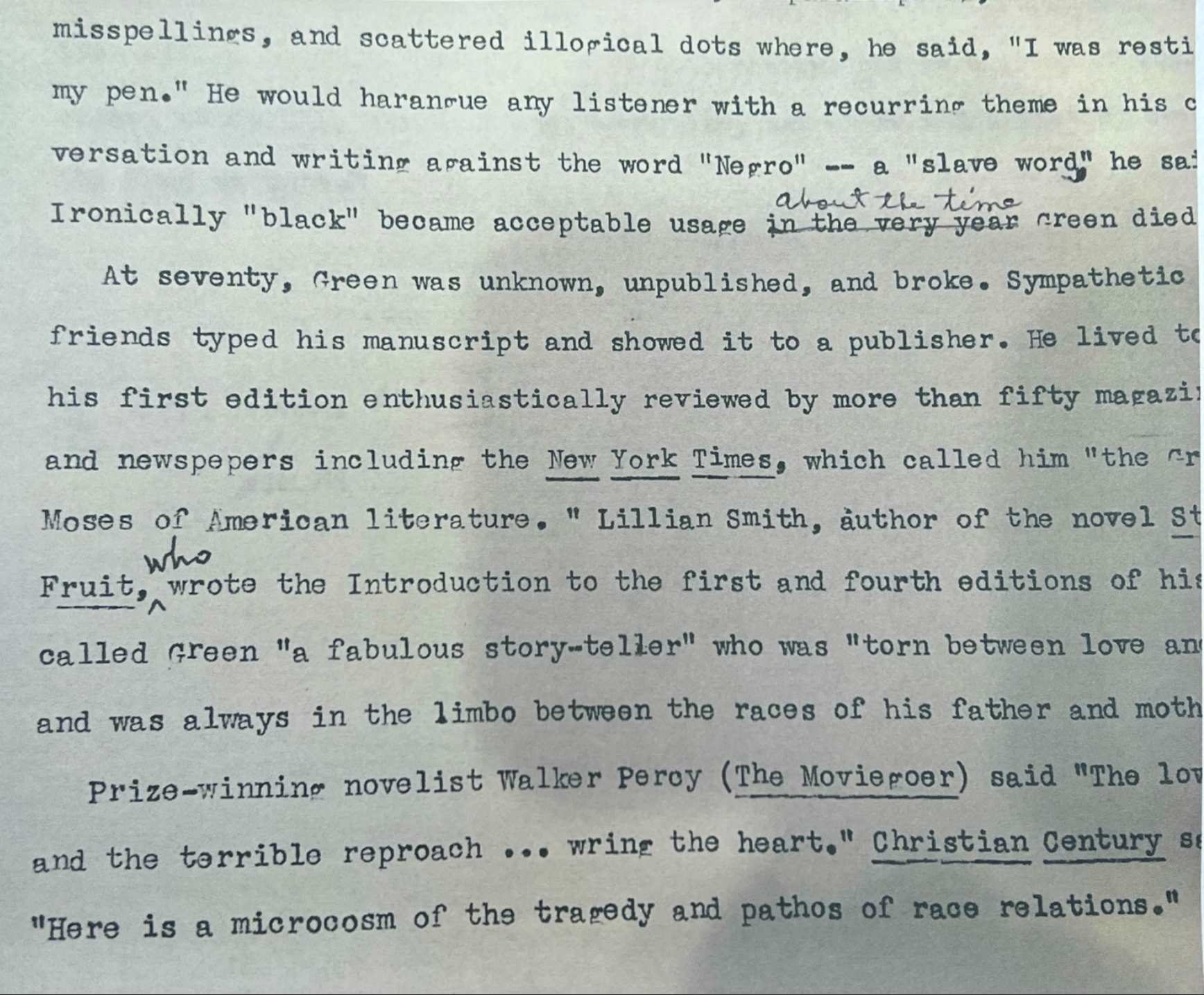

The following semester, I invited a new group of students to further explore the history of how Green’s story was adapted to appease the comforts of a moderately liberal white readership, as well as the Chittys’ string of rejections in their attempts to get Green’s manuscript—as the work of a Black writer—published by mainstream presses. I taught an upper-level English course alongside independent graduate study courses for Sewanee’s School of Letters, an MFA program. I had the undergraduates refine the diplomatic transcriptions first completed by the first-year students. I trained them in TEI-XML encoding, and we then we worked together to create a custom TEI-XML schema for the project. Once all was ready, we began encoding in Oxygen XML editor. An example feature of the custom schema includes the Unicode symbol that we determined best visually represented an interesting characteristic in Green’s handwriting. He would often write three dots typically in the shape of a triangle that represented, as Chitty claims, when Green was resting his pen. But, there is clearly a more intentional pattern to the three dots. They seemed to be used in the place of colons and periods and, at times, at the conclusion of a particular scene or reflection. We decided it was important to replicate this in the digital edition and so we found a Unicode symbol that looked very similar to the triangular three dots. Green also has moments where he does a vertical ellipsis, so we found a Unicode symbol code for that as well. Beyond encoding the manuscript line-by-line, students took a page-by-page inventory, noting persons, places, dates, and events that could be used for more advanced encoding endeavors in the future, such as XQuery.

With the graduate students, we investigated the theoretical and cultural-historical aspects of the project. They took the course as a literature seminar, so we focused on the literary history of Green's story by reading it within the context of the African American autobiographical canon. They composed research papers that will be featured on the project website. In these essays, they engaged in literary analysis to explore Green’s narrative voice while also using a cultural-historical lens to examine the ways in which white editors altered Green’s manuscript during the Civil Rights Era. To prepare my students for their essays, we discussed the decades-long effort the Chittys made to see Green’s story converted to the screen and in print. Ultimately, he all but completely failed. The Chittys must be highly commended for the countless time he spent in epistolary correspondence with editors, agents, and writers. Their representation of Green, however, is typical of a moderate white scholar in the 1960’s.

For instance, in a draft of Green’s 1999 entry in Oxford University Press’s American National Biography, we glimpse Arthur Ben Chitty’s typical interpretation and treatment of Green’s story: “His sole legacy is the 1,200 page autobiography (complete in the second edition) with its erratic punctuation, no paragraphing, hundreds of misspellings, and scattered illogical dots where, he said, ‘I was resting my pen’” (emphasis added). Chitty omitted “illogical” from the final draft. This alteration reveals the unconscious bias that often shaped Chitty’s representation of Green. At the same time, however, Chitty’s editorial decision to remove the word “illogical” suggests that he ultimately regretted that word choice and understood it to be a misrepresentation of Green’s abilities. In other words, his papers in the Archives reveal a tendency to appease the sensibilities of the white elites of the publishing industry that were discomforted by the prospect of publishing works by Black writers that might be too insightfully fixated on race relations in America. For instance, in a rejection letter from the famed Bennett Cerf, co-founder of Random House, Cerf states: “I must tell you frankly that there have been so many books published this year—with heaven knows many more already under contract—about the Negro problems in America, past and present, that we simply do not want to hear any more for some time to come.” Cerf goes on to list only two pending publications on the subject, one of which was written by a white author (The Confessions of Nat Turner by William Styron).

After the Sewanee Years publication by Seabury Press, Chitty was only able to see Green’s work published by academic presses. Even Seabury Press refused Chitty’s two requests to publish the full autobiography in 1967 and to reprint the Sewanee Years in 1980. As one graduate student observed: “It is interesting to note that Green’s story is adapted to survive in the literary marketplace, while he is adapting to how to survive in Sewanee.” Duality is a current that runs throughout this project. It is revealed in the bifurcated identity that Green struggles with during his lifetime, through his biracial status as well as the double consciousness of being African American as exemplified in his childhood dialogue with Uncle Tom. It is also evident in the way his story itself was censured by publishers and how the digital variorum endeavors to provide a lasting comparative tool between his written words and their attenuated derivatives.

Arthur Ben Chitty’s draft of Ely Green’s entry in the African American National Biography

Who's Behind the Project

Hannah Huber

Hannah Huber served as the Digital Technology Leader and Project Administrator for the Center for Southern Studies from 2020 to 2024. Prior to that, she received her PhD in English from the University of South Carolina and served as the postdoctoral research associate for the Digital Humanities Initiative at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She is currently an Instructor of English at Volunteer State Community College.

The Roberson Project on Slavery, Race, and Reconciliation, the University of the South

The Roberson Project memorializes the late Professor of History, Houston Bryan Roberson, who was the first tenured African American faculty member at the University of the South and the first to make African American history and culture the focus of his teaching and scholarship. The Roberson Project, directed by History Professor Woody Register, seeks to honor Roberson’s inspiring legacies by helping Sewanee’s campus confront its history in order to seek a more just and equitable future for our broad and diverse community. A special thanks goes to October Kamara, a PhD History student at the University of Illinois at Chicago whose digital humanities work with the Roberson Project helped chip away at the transcription and encoding process.

The Center for Southern Studies, the University of the South

The Center for Southern Studies, directed by English Professor John Grammer, is a Mellon Foundation-funded initiative committed to rigorous explorations of the Southern past, confronting the region's moral and practical failures as well as its achievements, in the hopes of informing a thoughtful critique of the present and an imagining of possible futures. The goal of the program is to encourage the interdisciplinary study of the U.S. South by the scholars who participate in its conferences and other academic occasions, by the post-doctoral Fellows it hosts, and by undergraduates at the University of the South.

Patricia Ravarra

Ely Green is the maternal grandfather of Patricia Ravarra, an award-winning artist and Fulbright scholar. Ravarra currently resides in Hawaii and is a long-distance supporter of the project here in Tennessee, which seeks to make her grandfather’s story more accessible by drawing focus to his written words and storytelling beyond the institutional archives and printed editions.

Em Turner Chitty

Em Turner Chitty recently retired from an academic career in English as a Second Language at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville and shares copyright ownership of the autobiography with Ravarra. Having inherited the decades-long stewardship of Green’s story from her parents, Arthur Ben and Elizabeth N. Chitty, Em Turner Chitty continues the work alongside and in collaboration with Ravarra.

“The Suitcase” Podcast Team

“The Suitcase” is a podcast currently in the works by a team comprised of April Alvarez (Associate Director, Sewanee School of Letters), Sam Worley (award-winning journalist and graduate of the Sewanee School of Letters), Karla Diggs (English Professor at Motlow State Community College, novelist, and Sewanee School of Letters student), and Hannah Huber. Learn more about the podcast here.