About the

Manuscript

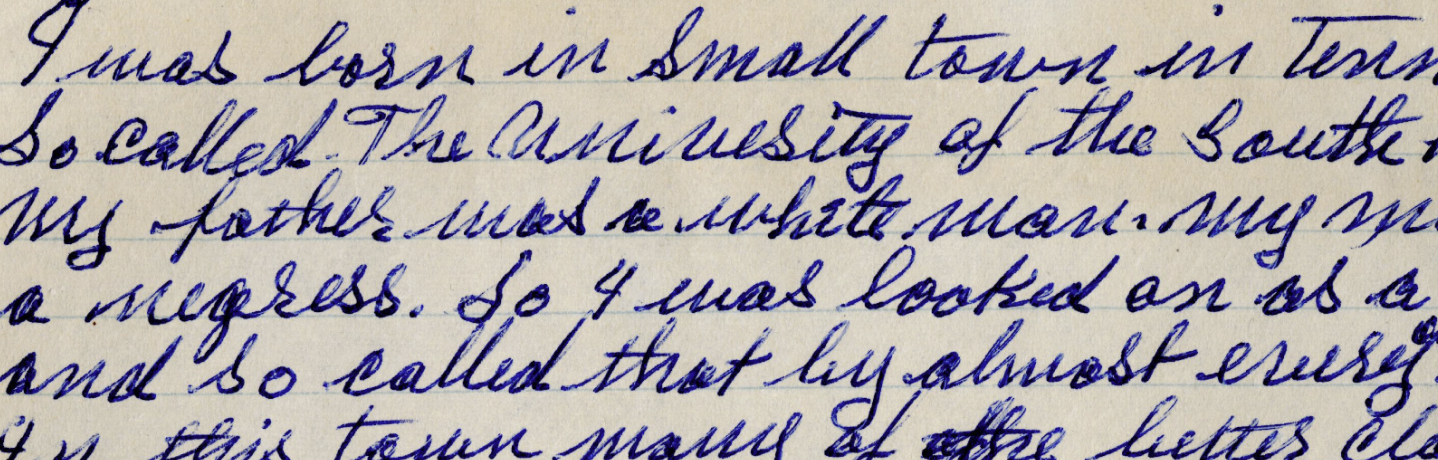

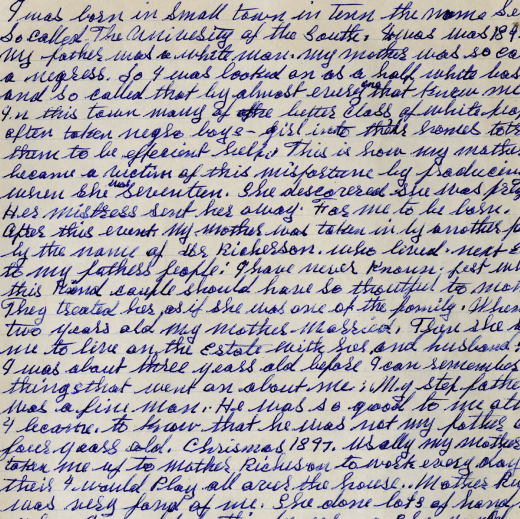

Green received only six months or so of formal education in his youth and taught himself to read and write as he came of age. As he honed his literacy in young adulthood, Green became a practiced chronicler of daily life. Despite two tragic incidents—one in which his diaries were used as evidence in a court hearing and never returned and another when a scorned lover absconded with his personal papers—Green was persistent in compiling his life story.

By 1964, Green had compiled over 1,200 handwritten pages. Having heard that a white historian was looking for Black stories about local Sewanee history, Green traveled from his home in Santa Monica, California to present a suitcase full of these papers to a historiographer at the University of the South, Arthur Ben Chitty and his wife Elizabeth Chitty. Chitty had received his Master of Arts in History at Tulane University and his thesis was a historical study of the Reconstruction Era at Sewanee. He and his wife, who went by Betty Nick, proved invaluable figures at Sewanee, for they served in many ways as official and unofficial custodians and preservers of Sewanee’s history. Unsurprisingly then, the couple was eager to help share Green’s story and facilitate the publication of the manuscript.

1966 Publication

Despite decades of endeavoring to see Green’s story in print and film, Chitty only succeeded in getting two editions of Green’s story published. The first was in 1966 by a small Episcopal publishing house, Seabury Press, and included only Green’s years in Sewanee (the first 220 or so pages of the manuscript). Elizabeth Chitty originally transcribed the handwritten manuscript, which contains no paragraph or chapter breaks. But, it was the Press and its editor at the time, Arthur Buckley, that handled the editing and formatting. Green suffered a debilitating stroke around this time and died in 1968, so he was never involved in the editorial process. The Seabury version altered, condensed, and divided the transcript to meet novelistic conventions with formal punctuation, paragraphs, and chapter breaks. It was directly reprinted by the University of Georgia Press in 1990, and it is this version that is still marketed to Sewanee students today (as the singular edition including only the Sewanee years).

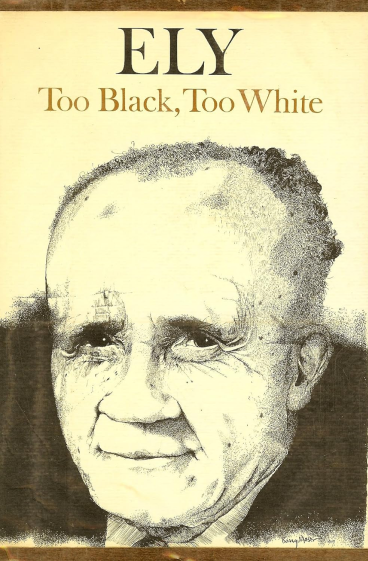

1970 Publication

The second publication facilitated by the Chittys appeared in 1970 from the University of Massachusetts Press. This time, Green’s original structure of eight sections was maintained and less passages were omitted. However, the autobiography as a whole was treated more as a historical document than a work of literature. By vetting and “correcting” the manuscript without any accompanying editorial record (neither edition provides notes explaining the changes that were made), the 1970 edition values the manuscript for its worth as a historical document much more so than it does as a product of memory, story-telling, and self-making. Ironically, both editions were altered to provide false names for prominent white families in Sewanee. For instance, Green’s white father is referred to with a fictitious name to protect the privacy of the family. Yet, there is no evidence of any Black names being likewise changed. Green’s mother was a domestic servant in a white household when she became pregnant with Green. It was common knowledge in Sewanee at the time that a son in that household, much older than Green’s mother, had raped and impregnated her. Green writes in his manuscript that his mother was seventeen at the time of his birth, but according to Arthur Ben Chitty in a letter to an editor at the University of Massachusetts Press, Green told him that she was fourteen at the time. The reason for this discrepancy is unknown, but possibilities range from Green wanting to protect his mother’s privacy to his being all too aware of the sensibilities of the kind of readership to which his book would be marketed. Yet, while Chitty exercised discretion in changing the family name of Green’s father, he encouraged the University of Massachusetts Press to show no such prudence in asking them to change her age to fourteen. The Press must have decided to represent the age as Green wrote it, as they kept it as seventeen. Decades later, Chitty would take it upon himself to note her age as fourteen in his 1999 entry for Green in Oxford University Press’s American National Biography. Furthermore, in publicity surrounding the publications throughout the years, Green’s mother is named but never his father.

The Chittys should be celebrated for bringing Ely Green’s story to light, and it is evident from the several decades that Arthur Ben Chitty spent promoting Green’s work that Green and his story meant a great deal to the Chittys. Therefore, the goal of the Ely Green Digital Variorum (EGDV)—in its effort to un-edit Green’s story—is not to identify specific agents who acted upon Green’s manuscript with racist intentions but rather to reveal and explore the complexities of institutions of power, from the historically white elitism of Sewanee to the publication industry (intent on appeasing, at most, a moderately liberal, white readership), that would only accommodate Green’s story in an attenuated, more palatable form. This project poses the following questions: How can we deal with these concerns by returning to the manuscript? How do we identify these variations and changes? How can we visualize them and make sense of them? Are their trends and patterns to be discovered that tell us about why these alterations were made? The EGDV is an attempt to answer these questions by serving as a digital edition of Green’s diplomatically transcribed manuscript displayed alongside its published derivatives.